High Noon

Green Cardamom

We hear a lot – perhaps too much – about ‘identity’ in relation to South Asian art. Whether it’s national or personal, this elusive quality is often seen as the primary concern of South Asian writers and visual artists, to the exclusion of all other aesthetic categories. By contrast, those who can lay claim to sufficient whiteness or Westernness are presumed to be the unreflective owners of secure but troublingly authoritarian identities whose dismantling is the proper task of progressive artistic practice. It’s a formulation which has, after a generation or so of post-colonial criticism, become an orthodoxy.

High Noon, as the title suggests, stages a confrontation with this brittle identity politics and claims a kind of luminous clarity, where shadows and ambiguities disappear. Noon is when mad dogs and Englishmen are the only creatures out on the street. High NOON is also a punning physicist’s term for certain states of quantum superposition, when particles exist in both of two possible states, so perhaps there’s also a suggestion of kairos in the title, the ‘time of chance’, that suspended moment when decisive action may bring about great and significant change. Clearly, for Pakistan, such a time is at hand.

Whether Pakistani artists like it or not, the question of their identity now has geopolitical significance. Who are the inhabitants of this young country? What do they believe? Unmanned drones hover over the North West Frontier to mete out punishment to those who answer incorrectly, while men who have no time for representation of any kind, and who hate art for its advance into the territory of religion, are waiting in the wings. As the confusion and carnage on Pakistan’s northern border threatens to move southwards, the longstanding preoccupations of post-colonial cultural politics are pushed aside by more pressing concerns.

It may be that it’s only possible to wage war on those whom one doesn’t see fully, those whom one allows or forces oneself to view as less than human. This suggests that – seen now, in 2010 – the art in this collection has a particular urgency that exists as much in the desire to trace small, personal actions (getting dressed, drawing a line), as in overtly political gestures, such as the arresting opening image in which a woman hangs her blood-red washing out to dry on the wings of a decommissioned fighter plane. The machismo of the military, which has played such a decisive (and often disastrous) role in the history of Pakistan, is one factor at work in this time of chance. So is the public space of the street. What does it mean to turn private, domestic life (ironing, reading a newspaper) out on to the eerily empty roadways of Ramadan? What relationships do such actions have to the other uses of the street – as a place of protest, or commerce, or as the setting for an Independence Day parade? A wall stained with betel-spit is a modest testimony to the accretion of history, a guttural desi riposte to the vast canvases of Anselm Kiefer, with their caking of European ash and dust. Sometimes one feels the artists have internalized the categories of post-colonialism and are now doing what is expected of them as Pakistani artists, by reproducing them in the hope of critical approbation. Yet even the failure to represent oneself authentically, the impossibility of seeing oneself except as belated, constructed, supplicatory, is significant.

Right now we need more than news images, but representation of any kind feels inadequate in the face of the vast material forces driving the region towards conflict. The paradox is that the most fugitive, fleeting traces of humanity – melancholy petals painted in watercolour on a marble floor – may outlast those forces. The floor is in Kabul. The light falls across it, striating the painting with bars of shadow. What is pigment? What is light? Time is passing, quickly.

by Hari Kunzru

Captions

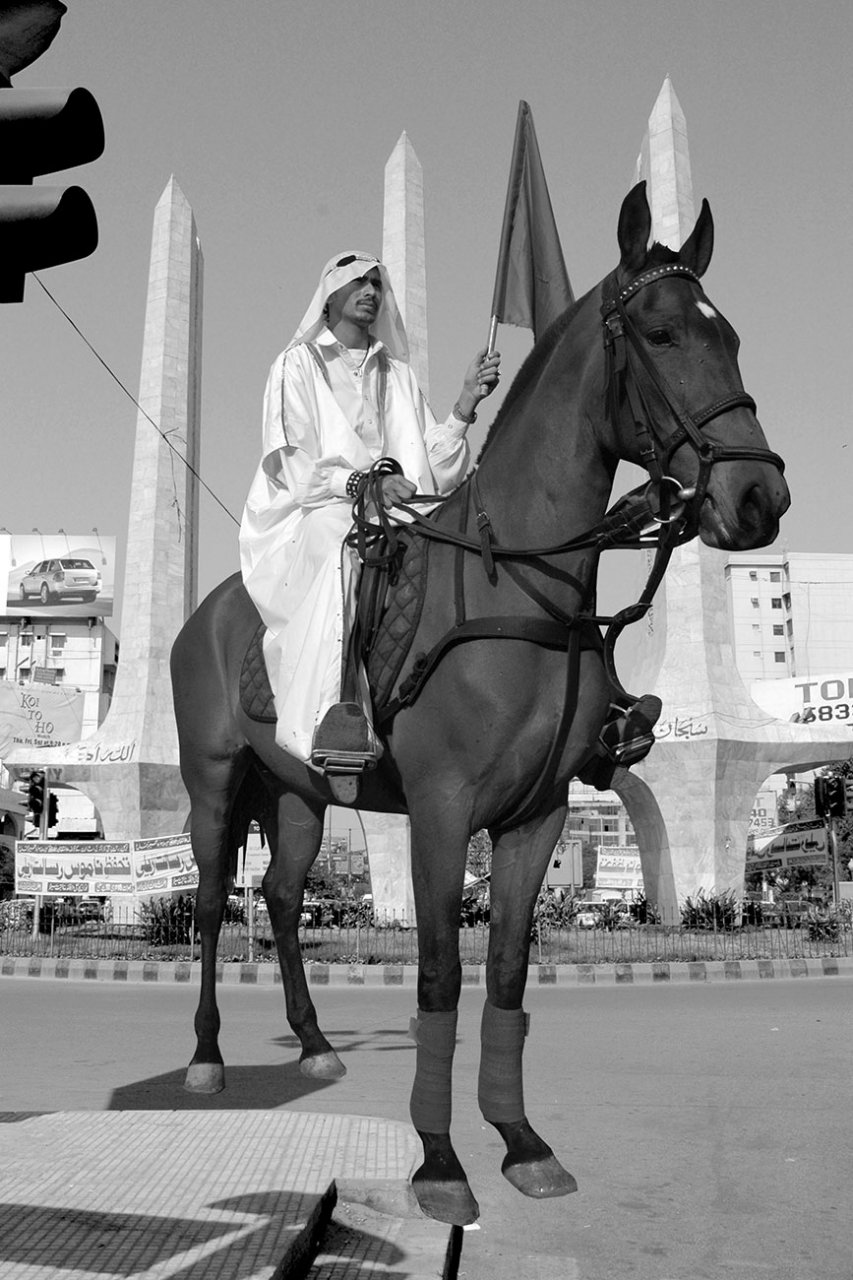

1. Bani Abidi (first image)

Edition of 5. Inkjet prints on archival paper, 28 x 18.5cm each (x9).

Loaded with cultural representation, this body of work deploys fiction to subvert meaning and destabilize dominant myths of national origin. A quixotic young man – ostensibly a young Christian convert to Islam – makes incongruous appearances in public places dressed as the Arab hero Mohammad bin Qasim. In this particular image he is photoshopped against the landmark ‘Teen Talwar’ (three swords) in Karachi, meant to represent ‘Unity, Faith and Discipline’, a secular motto attributed to Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

2. Ayesha Jatoi

Dyed garments on fighter jet, C-print, photograph of installation/performance. Image courtesy of the artist and Asif Khan.

Decommissioned aircraft and armaments – missile casings, old jets and once even a massive submarine – are frequently installed as public monuments, indicative of the presence of the military in the civic realm. In this performative act of resistance, the artist washed a load of red garments and then draped them across the aircraft to dry.

3. Bani Abidi

Duratrans Lightbox, 50.8 x 76.2cm each.

At dusk during the month of Ramadan most Muslims in Karachi are breaking their fasts, leaving the streets eerily empty. Abidi imaginatively reclaims public space by allowing the streets to be occupied by ordinary citizens from religious minorities – Hindu, Parsi (Zoroastrian) and Christian – who are part of the shared history of the city, but increasingly less visible.

4. Rashid Rana

Edition of 10, C-print, Diasec, 194 x 197cm.

This is a composite image of photographs that could be from a video or a stop-motion animation. Frame by frame, the artist dresses himself, changing garb several times, reinventing his image. In the ‘mirror’ image the process is reversed, but does not correspond perfectly, creating a sense of dissonance.

Site-specific installation, Qasr-e-Malika (Queen’s Palace) Bagh-e-Babur, Kabul, Afghanistan.

Emulsion and acrylics on marble floor and walls. Image courtesy of the artist and Turquoise Mountain, Afghanistan. Qureshi uses the motif of foliage from traditional miniatures as a form, a weedy organic growth that seeps into architectural space. This installation in Kabul interacted with the play of light from the windows on the gallery floor, shifting the image with the passage of time.

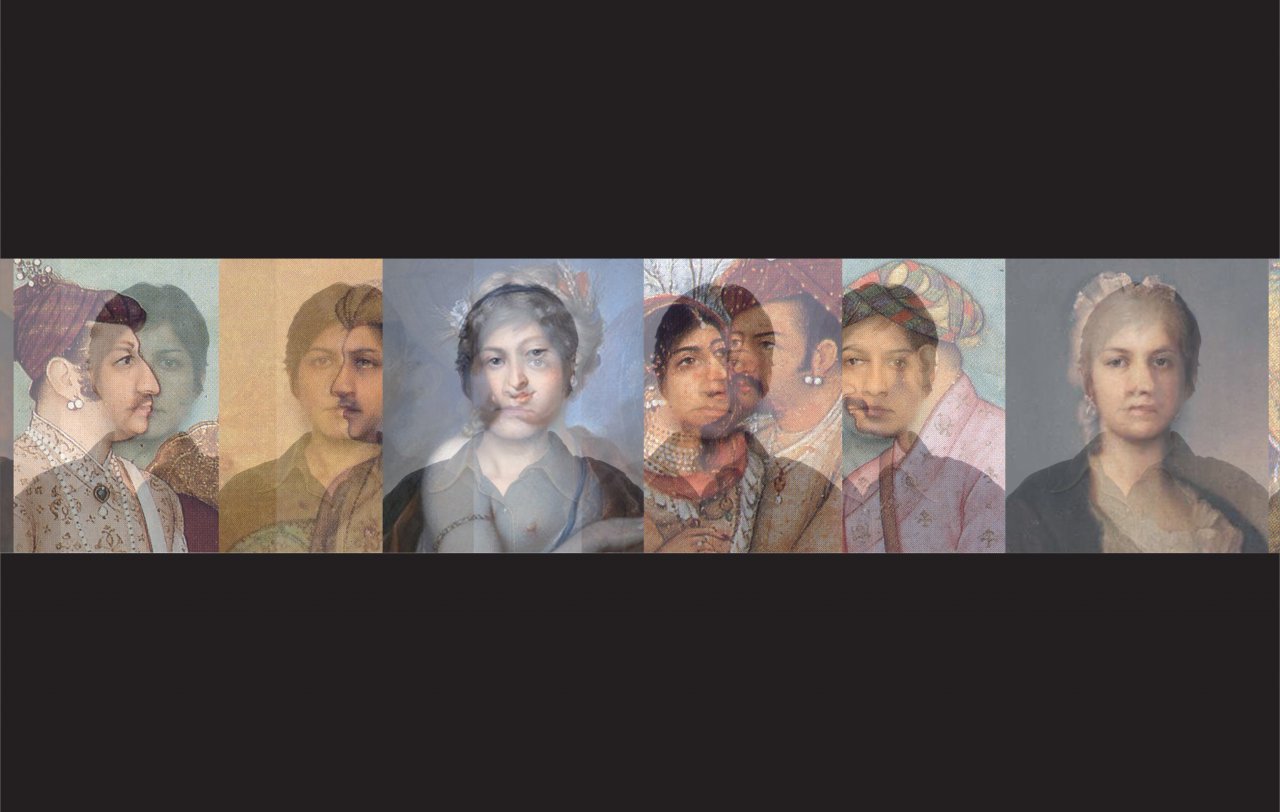

Digital print on transparent film, 65 x 870cm.

Qureshi’s practice deals critically with the politics of representation, fragmenting dominant historical narratives. Borrowed images are reappropriated and transformed, obscuring or refusing their original meaning. This work is a combination of the artist’s own ID photos, Moghul miniature portraits, early colonial photography and portraits by Venetian painters.

C-print Diasec, 64 x 52cm.

A suite of photographs of Urdu-language films shown on state-controlled television in the 1970s, examining television as a way of imagining and shaping collective ideas of ‘success’ or ‘urban modernity’ as exemplified by the interiors, fashion, personae and gestures of the films. Taken at slow shutter speeds, they capture scanning lines of the television screen and produce a grainy, blurred effect that suggests a dream or trance-like state, several steps removed from the ‘reality’ of the depicted scenes.

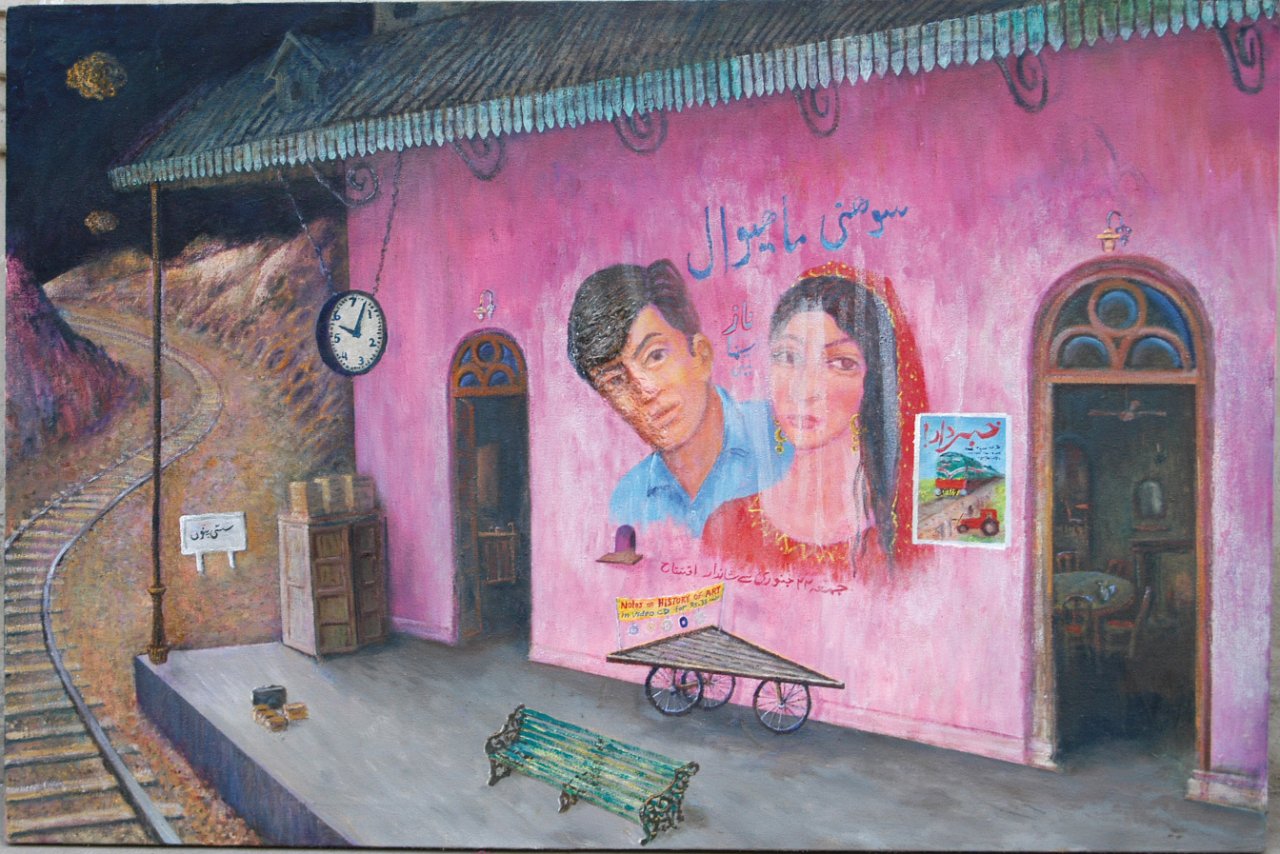

8. Mansur Salim

Oil on canvas, 81 x 122cm. Image courtesy of the artist and ArtChowk.

Mansur Salim’s surreal subjects include landscapes on a fictional planet, a space loaded with magical symbolism, layered with nostalgic memories, art-historical references, vernacular mythology and mathematical riddles. Disrupting notions of time and the context of place, this work is named after the ill-fated lovers in the Punjabi tale, while the faces strongly resemble film stars from the 1970s.

9. Mehreen Murtaza

Archival C-prints, 38.1 x 38.1cm. Courtesy of the artist and Grey Noise.

From a series of a dozen digital collages in which Murtaza playfully examines the latent presence of technology in urban visual space, merging globalized modernity with local landscapes. Referencing old war films or sci-fi fantasies, she creates charged images with a lurking sense of the absurd.

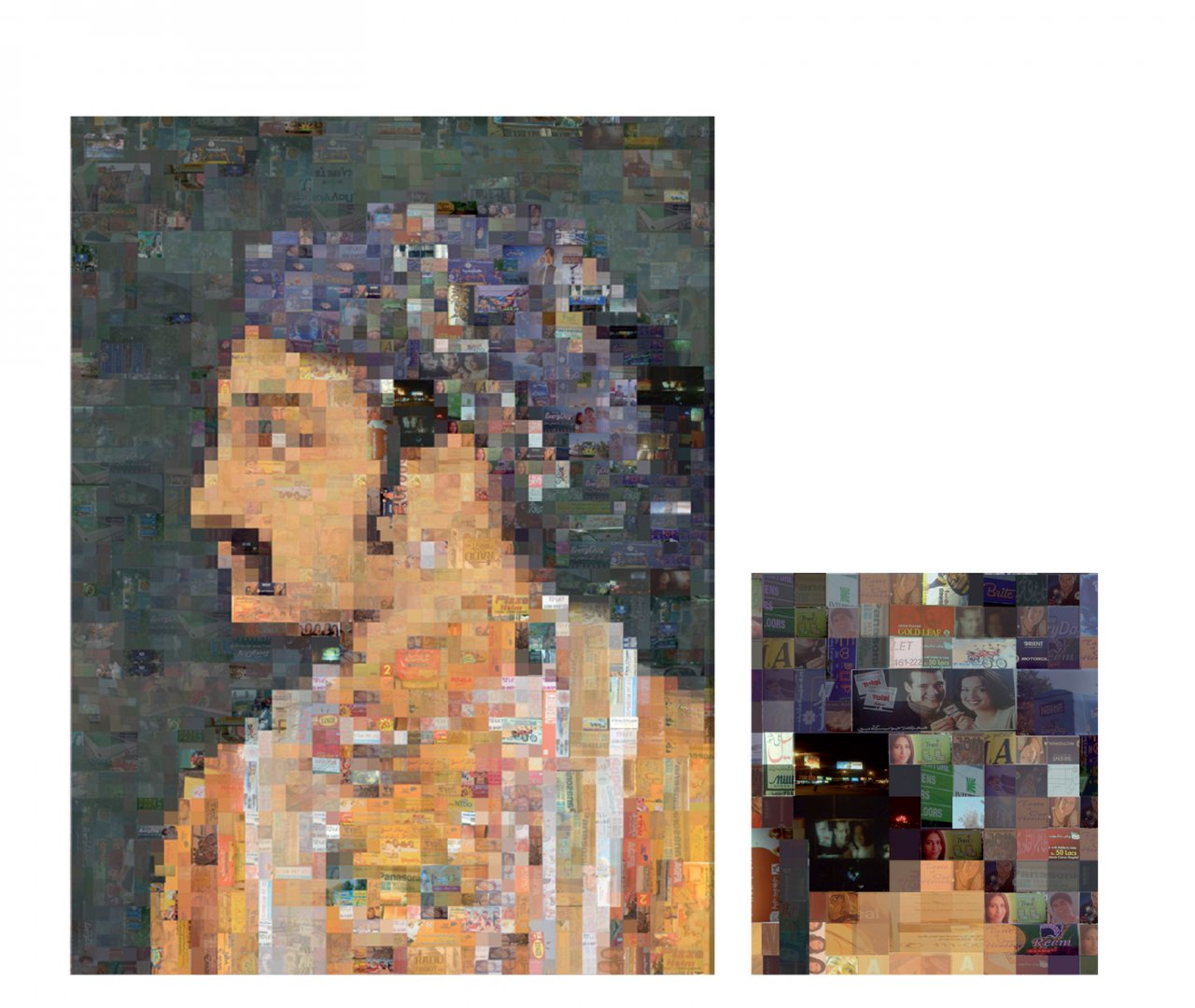

10. Rashid Rana

Edition of 20. C-print, Diasec, gilt frame. 45 x 35cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

At first a conventional portrait of the Moghul emperor Shah Jehan, on closer inspection the image reveals itself to be composed of photographs of billboards from the streets of Lahore, challenging exalted cultural forms by reconstructing them with visuals collected from the everyday.

11. Naeem Mohaiemen

Set of 5 digital prints, 6 x 61cm each. Installation of postage stamps from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, sizes variable, displayed on white plinth. 30 x 30 x 100cm. Image courtesy of the artist and collection of Raffi Vartanian. Commissioned for Lines of Control, a Green Cardamom project.

Three sets of stamps, from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, all bearing the image of Kazi Nazrul Islam, a revolutionary poet claimed by all three nations as a national symbol. The first four images are of the fierce, grimacing eyes of Nazrul as he was forced to pose for official photographs, unable to voice his refusal due to a mysterious disease which affected his speech and memory. The last image is of General Ziaur Rehman of Bangladesh at Nazrul’s official funeral, which took place in Bangladesh against his own wishes and those of his family in India.

12. Muhammad Zeeshan

Digital print on canvas, 91.5 x 55.9cm.

A found urban image photographed by the artist, part of a series of abstract ‘paintings’ created by splatters of peekh on city streets, which are more visible on the footpaths and alleys in lower-income areas. Peekh is the spat-out juice of the paan leaf, commonly chewed with tobacco as a mild relaxant.

Acrylic and oil on slate, 18 x 22.5cm each.

Slates and chalk are used widely in rural and lower-income government school environments as rudimentary writing materials. History, erasures, memory and nostalgia are all themes that the artist explores. The top figure is Seth Naomul Hotchund – a prominent Hindu trader rewarded by the British for his services to the Crown and considered a traitor by Muslim landlords and Talpur rulers of Sindh in the nineteenth century.

Printer’s ink on paper, 75 x 55cm.

Talpur used a mechanical printing press as an instrument to ‘draw’, varying the process to produce a series of works based on the form of the common exercise book. Although produced by a machine, the work registers a strong presence of the artist’s hand and his desire to subvert the predictable. This particular piece combines the formats used to write in Urdu (upper half) and in English (lower half), reversing the linguistic and class order determined by access to education. All images, unless otherwise specified, are courtesy of Green Cardamom and the copyright of the artist.

The images in the issue are a collaboration between Granta and Green Cardamom curators Hammad Nasar, Anita Dawood and Nada Raza.

All images, unless otherwise specifid, are courtesy of Green Cardamom and the copyright of the artist.